Elmyr, The True Picture

Posted on November 16, 2022

by Mark Forgy

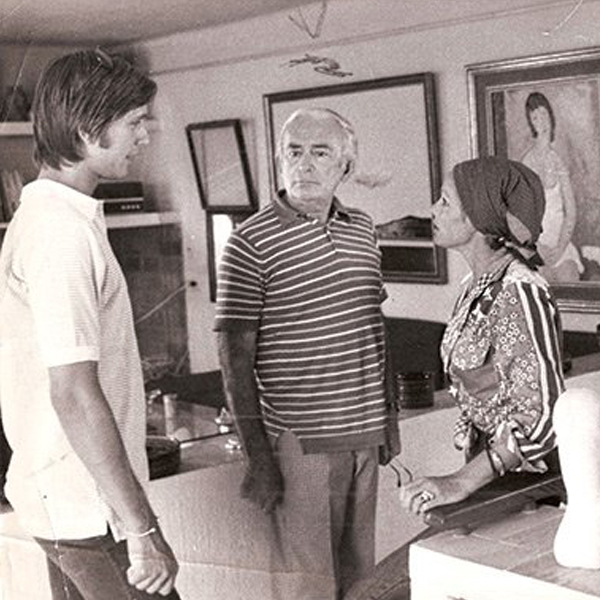

This film features artist/art forger Elmyr de Hory and Mark Forgy. It offers the best footage ever taken of de Hory, presents intimate, personal insights into the man who authored the greatest art scandal of the twentieth century.

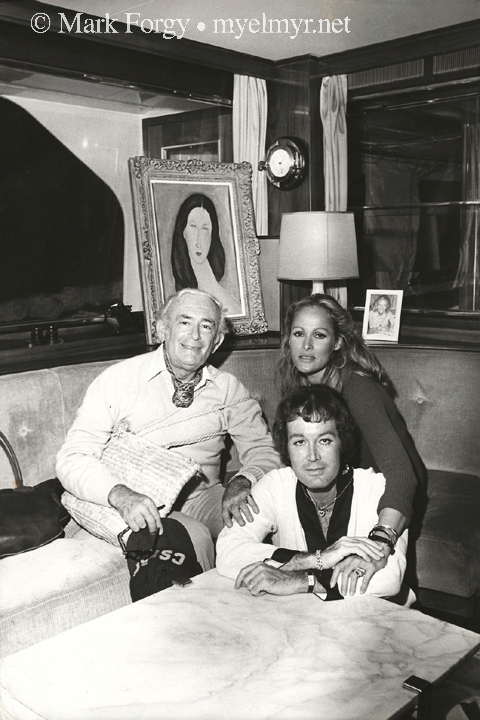

The Relationship Between Elmyr and Ursula Andress

Posted on August 8, 2022

by Mark Forgy

This film features artist/art forger Elmyr de Hory and Mark Forgy. It offers the best footage ever taken of de Hory, presents intimate, personal insights into the man who authored the greatest art scandal of the twentieth century.

I first met the actress Ursula Andress in the spring of 1970. She was the first Bond girl in Dr. No

in 1962. The film’s sequence in which she emerges in a white bikini from Caribbean waters

made her an instant superstar and sex goddess of mythic stature.

What I couldn’t see coming was the twist of fate that allowed a friendship between us, one that

left me wondering how blessed and unworthy I was. However, Ursula was a longtime friend of

Elmyr’s before she became a movie star. Swiss by birth and work ethic, she was grounded, had

a self-effacing nature, completely without guile, genuinely kind and generous.

By the early 1960s Elmyr had discovered the quaint island of Ibiza, a sanctuary for artists

seduced by its beauty and friendly to escapees from urban hustle and bustle in favor of a more

bucolic Bohemian life. Ursula abandoned Beverly Hills for a secluded refuge there, unbothered

by paparazzi her fame had intruded on her life.

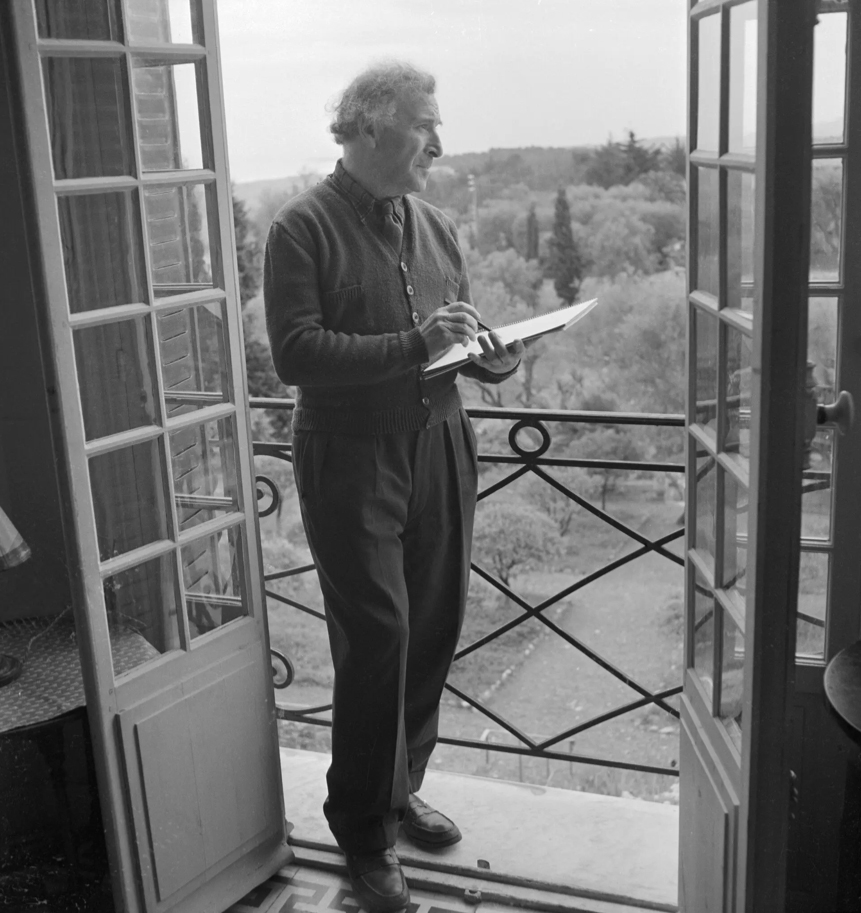

These photos were taken the day I met her for the first time at Elmyr’s home, La Falaise. At that

time Elmyr’s rarefied world of writers, artists, theater and film stars, intellectuals and beautiful

people, became a lifestyle distant from my working class upbringing in Midwest America. It was

a reeducation I never dreamed of.

At the same time, Ibiza’s cachet began attracting French aristocrats, former denizens of the

Côte d’Azur fleeing the overcrowding along the French Riviera. Elmyr’s passion for name

dropping, especially for those with titles, flourished. He could negotiate the convoluted family

trees of European royalty with the deftness of a ring-tailed lemur. It was an important slice of

genealogy to him and he expected me to accord it a similar importance, though it collided with

my democratic instincts.

My initial impression was that he was a snob. What I began to better understand was that was

not the case. It was his way of showing his connection to people. Everything — history, art,

literature, culture, travel, could be better appreciated as a tapestry of human relationships, the

fabric that wove it all together. Only much later I learned another contradiction — that art was

not his raison d’etre. His love of people was his greatest source of joy — and disappointment.

Moreover, his worldliness and sophistication lent no defense for misplaced trust and I could not

protect him from errors of judgment. Even when people or circumstances raised my suspicions,

I deferred to his decisions, thinking his wisdom and age surpassed my life experience. Then, he

lived by his wits his entire life. How could I offer any insights that life’s lessons had not already

taught him? It took a long time before I felt confident enough to offer any counsel of merit. In the

meantime, my role was to listen, observe and learn. Elmyr was my guru and I his acolyte.

Her ‘Chagall’ is Headed for the Trash. How’s That for Caveat Emptor?

Posted on July 6, 2022

by Colin Moynihan

The question of whether a valuable artwork is genuine can be surprisingly fluid, changing over time based on evolving and sometime competing evaluations.

In 1973, for example, the Metropolitan Museum of Art reattributed roughly 300 paintings in its collection, including works long thought to have been created by masters such as Rembrandt, Goya, Vermeer and Velázquez.

“I believe that attributions are like medicine or any field in which knowledge is constantly changing or advancing,” offered Everett Fahy, the Met’s curator of European paintings at that time.

Some 37 years later, the museum decided it had actually been right the first time around, and flipped back the attribution for one of those works, a portrait of Phillip IV by Velázquez.

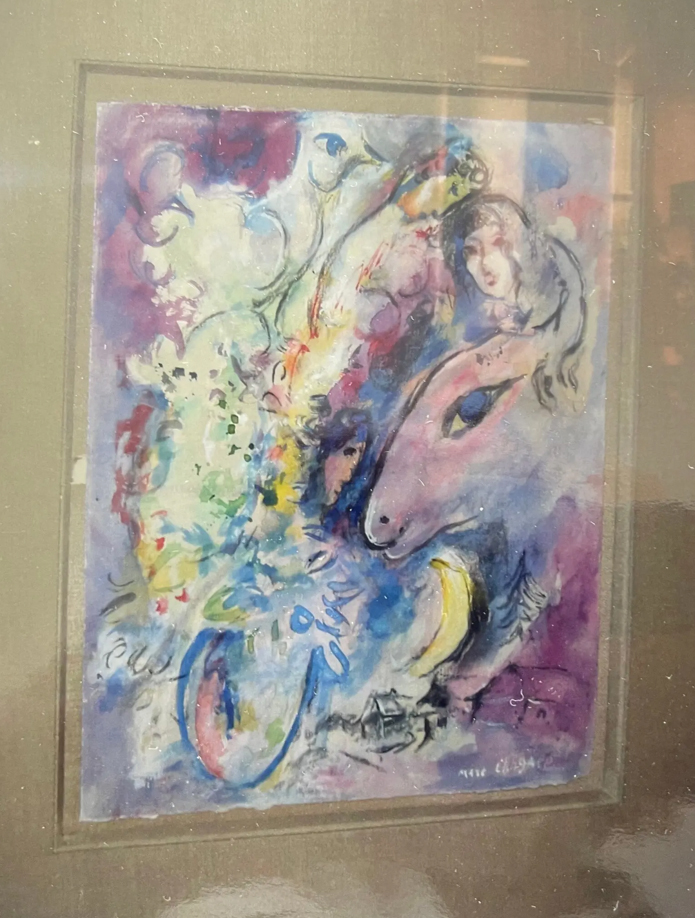

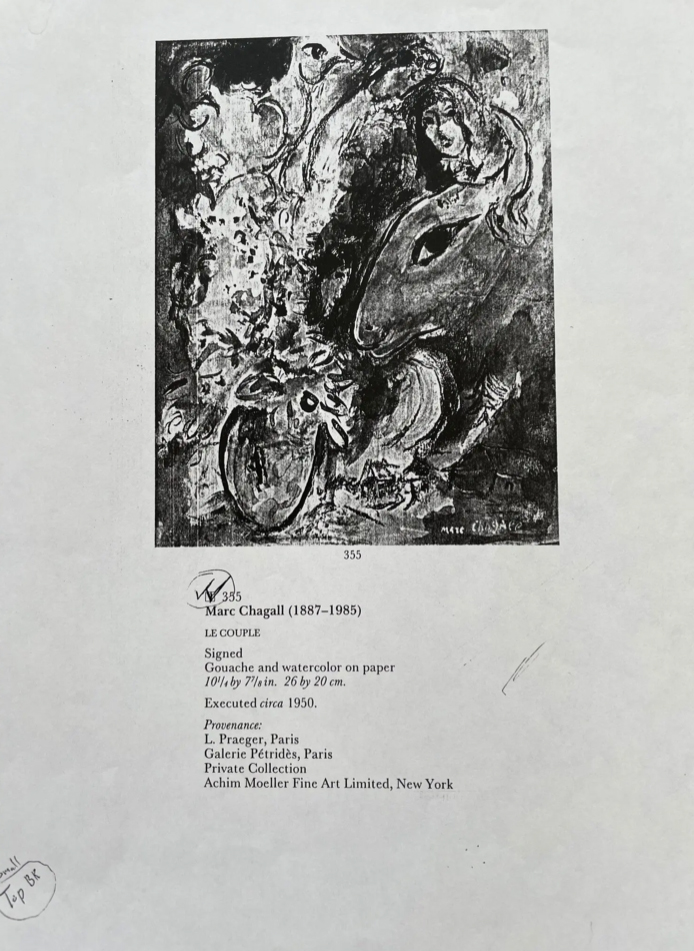

But this sort of history is of little solace to Stephanie Clegg, who paid $90,000 for a painting attributed to Marc Chagall at auction at Sotheby’s in 1994, just nine years after the artist’s death.

Two years ago, when she was looking to sell works from her collection, Sotheby’s suggested it might be a good time to auction her Chagall, among others, Ms. Clegg said. But the company told her it would have to send the work to France for authentication by a panel of Chagall experts.

Sotheby’s described the review as a formality, Ms. Clegg said, and she agreed, deciding that she had little reason to worry. The auction house, after all, had sold the work at auction as a Chagall and raised no doubt as to its attribution in 2008 when it reappraised the watercolor at a value of $100,000.

But, to Ms. Clegg’s dismay, the expert panel in Paris declared her Chagall to be fake, held onto it and now wants to destroy it.

When she complained to Sotheby’s, the auction house said there was little it could do, saying its guarantee of authenticity was good only for a time. The company has offered her an $18,500 credit toward their fee on any future sales of artworks she owns, a gesture that she calls inadequate.

“I trusted them through all those years,” Ms. Clegg, 73, said in an interview. “They were supposed to be reputable experts and I relied on their expertise.”

Ms. Clegg’s painting included “iconographic elements” of the

artist’s work but had not been created by the artist.

Now Ms. Clegg is in a standoff. Through her lawyer, she has asked Sotheby’s for $175,000. The auction house says there is no legal basis for that request and that the discount it has offered on future sales would match the fee it earned from the 1994 sale of the painting.

“Given that the initial sale took place well over twenty years ago, we are far outside the period of time during which Sotheby’s guaranteed the authorship of the work and would have had any recourse with the seller,” an auction house executive told Ms. Clegg in a 2020 letter.

Among the vagaries that make the art world such a compelling, if risky, marketplace is the fact that a change in attribution can sink the value of one work, or swell the value of another. Case in point: the “Salvator Mundi,” which reportedly sold at auction in 2005 for $1,175 when it was thought to be by a nobody, and then soared to sell for $450 million in 2017, after several experts decided it was the work of Leonardo da Vinci.

Auction houses have sought to reduce their exposure to unfavorable changes in attribution by limiting the time they will guarantee that a work is genuine. In Sotheby’s case, it tells buyers that it will warrant the work for five years. (Art galleries can set terms of sales in a contract, but are generally bound by the Uniform Commercial Code, which gives buyers four years to sue on the grounds that the authorship of a work was inaccurate or misrepresented.)

Ms. Clegg contends Sotheby’s bears more responsibility than it is accepting for the situation she is in, given its extensive involvement with the painting — as the original auction house, subsequent appraiser and recent adviser on its potential resale. Earlier this year her lawyer, Carter A. Reich, accused the auction house in a letter of “breach of contract, fraudulent misrepresentation, negligence and breach of fiduciary duty.”

Lawyers for Sotheby’s have denied all those claims, arguing that the auction house acted responsibly and in accord with its standards and procedures.

Ms. Clegg has held onto the page from the 1994 Sotheby’s catalog that advertised the work, a signed watercolor and gouache on paper titled “Le couple au bouquet de fleurs.” The catalog said Chagall had created it around 1950 and it listed the painting’s previous owners as L. Praeger, Galerie Pétridès, both of Paris; a private collection; and then Achim Moeller Fine Art Limited in New York.

In an email message, Achim Moeller said he had no memory of being involved with that work but added through his lawyer that he would research his gallery records.

Sotheby’s pointed out in a statement that, while it is rare, there are occasions when new and revised scholarship results in works being deemed inauthentic, something the auction house does not make assurances against.

“Sotheby’s respects and maintains the confidentiality of its consignors and buyers, and does not comment on matters that are not of public record,” the statement said, adding: “This particular work was known to the market, and was traded multiple times prior to the auction in 1994.”

identified the painting as a Chagall and listed a provenance for the work.

The Chagall hung for years on the wall of the bedroom that Ms. Clegg shared with her husband, Alfred John Clegg, before going into storage when she moved to a smaller home. That’s where it was, she said, when Sotheby’s suggested in early 2020 that if she were interested in selling items, her Chagall, among others, might do well. The work was subsequently shipped to the Comité Marc Chagall, a panel of experts that was founded in 1988 and which makes decisions on the authenticity of works attributed to the artist.

In late 2020, the panel released its findings regarding her work. In a letter to Ms. Clegg, Meret Meyer, one of Chagall’s granddaughters and a member of the panel, reported that it had unanimously found the work to be inauthentic, adding that it is an amalgam of several other works including “Le couple au bouquet,” from about 1952, and “Les amoureux au cheval” from 1961.

Ms. Clegg’s painting included “recurrent iconographic elements of Chagall’s work,” including a bouquet, lovers, a horse profile, a rooster profile, a village silhouette and a crescent moon, the committee wrote, but those lacked “real presence,” according to a translation provided by Ms. Clegg’s lawyer. The letter went on to say that Chagall’s heirs were requesting the “judicial seizure” of the painting “so that the work may be destroyed.”

In France, courts have recognized the authority of expert panels to destroy works determined to be counterfeit.

Nearly a decade ago, the Chagall panel moved to destroy a work, “Nude 1909-10,” that a British businessman, Martin Lang, had bought in 1992 for 100,000 British pounds, thinking it was by Chagall, the BBC reported. Mr. Lang objected, but then tweeted in early 2014: “I have decided not to fight this expensive court battle! These committees lack human compassion!”

Thomas C. Danziger, an art market lawyer in Manhattan who is not involved in Ms. Clegg’s case and has not examined her painting, said the authority of a panel like the Chagall committee is absolute when it comes to the market.

“You could have a photograph of Chagall painting this,” he said, “and have his own written testimony that he did, but if the Comité says it’s not by the artist then, for the purposes of the art market, it’s not by the artist.”

been created.

Bettmann/Getty Images

Given that history shows attributions can change, the idea of destroying an artwork strikes some experts as too final.

“If the premise is that the authenticity can change when experts change, destroying a painting takes away that possibility,” said Jo Backer Laird, a lawyer who spent 10 years as general counsel for Christie’s auction house.

Several authentication committees have been sued after ruling that a work was not genuine and panels that officially reviewed the works by Jean-Michel Basquiat, Andy Warhol and Jackson Pollock have disbanded. Ms. Clegg’s lawyer, Mr. Reich, declined to comment on the possibility of suing the Chagall committee.

Ms. Clegg has instead pursued Sotheby’s. In a letter to the auction house, Mr. Reich wrote that it had “falsely and recklessly assured” her that the committee rarely seized works and that she had nothing to worry about. He also wrote that Sotheby’s had told Ms. Clegg “additional research would be conducted” before the painting was sent to the committee, but that no research was performed.

In rejecting the claim that it bears responsibility for Ms. Clegg’s situation, Sotheby’s isn’t relying solely on the fact that the auction house’s warranty of authenticity had expired. Sotheby’s also has said through its lawyers that it apprised Ms. Clegg in writing of the risks of submission to the committee. They added that any statements to Ms. Clegg about the likelihood of seizure by the Chagall panel were only expressing expectations, noting that she had signed a release indemnifying Sotheby’s from any claims connected to that submission.

Sotheby’s lawyers further argued that the committee had not begun regularly issuing certificates of authenticity until the mid- to late 1990s, suggesting that the auction house had not been able to seek that level of certainty before the 1994 auction.

Mr. Reich said he questions that assertion, given the fact that the committee’s letter to Ms. Clegg included a line that read: “It is pointed out that in 1994 the MARC CHAGALL COMMITTEE was not brought to examine the work presented either before or after the sale.”

Ms. Meyer of the committee did not address a question about whether the panel was regularly authenticating works in 1994.

Mr. Reich said that, even if the committee was not then regularly authenticating work, it certainly was by 2008, when Ms. Clegg, who goes by the name Stevie, asked Sotheby’s for an updated evaluation of the Chagall.

“How could Sotheby’s appraise the work for $100,000 (or for any amount?) without mentioning anything to Stevie about the need to have it authenticated?” he asked.

Sotheby’s said that documents related to that appraisal made it clear that its valuations were provisional and subject to further research and authentication.

For Ms. Clegg the matter boils down to a simple formulation.

“I bought this painting through Sotheby’s as an authentic painting at the authentic price,” she said. “I think they should stand by that.”

Self-Interest: Our Most Comfortable Sin

by Mark Forgy

I found myself in an odd but familiar role of defending someone close to me while acknowledging his storied but criminal past. The optics of defending the indefensible are always a hard sell. In these instances our reactions are to parry emotionally charged issues with reason or rationalization that mitigate any bad act. And our impulse to shed accountability begins early in life. I recall my own childhood transgressions, feigning innocence with a chocolate-smeared face, being asked, “Did you eat the cookies?” Even when all indicators point to culpability, denial and deception are our frontline defense, our go-to strategies of self-protection… and those instincts are primal. Survival begins with selfishness.

A radio program out of Brigham Young University called Constant Wonder asked if I was interested in doing an interview. My longtime association with an art forger prompted the invitation. His name was Elmyr (pronounced el-MEER) de Hory. In 1967 the biggest art scandal of the twentieth century identified him as the author of an untold number of fake works attributed to a host of modern masters. He made fools of the experts, profited from fraud and wrapped himself in the mantle of ‘iconoclast’, a kind of Martin Luther-cum-Robbin Hood. De Hory’s intent to deceive was more often a source of entertainment than upset from what I observed. One common view transformed him from art criminal to folk hero, pulling back the curtain of artifice and pretense of the Art World, his role as outlaw a trifle detail.

Soon after meeting Elmyr, he told me he was an artist. No caveat followed, nothing about him being wanted by the FBI or his claim to fame. He was looking for someone to work as his personal assistant. “Are you interested in the job?” he asked. It was an invitation I couldn’t refuse, though only a few days had passed since our encounter. A few weeks later I found out the truth about him, his reputation, and said to myself “Oh, my God, I’m living with an art forger. How cool is that?”

The man I knew as worldly but self-effacing and low-key, became a bad-boy media darling, portrayed as a talented rascal in the popular press; that moved the conversation from him being a law breaker to rock star-provocateur. Criminal turned celebrity. He heard only the applause and viewed his notoriety as a stamp of public approval of his crimes. I watched as his life in the shadows eased into the spotlight. His delight in becoming a personage was palpable. What he didn’t realize was that his renown left a mark. He emerged from his two-decade-long illicit career, hoping his artistic skill would find an audience for his own art.

“Fame bends the light through which we view creativity,” as someone said. The same could be said of infamy. He often described himself as “famously infamous.“ So, those who were drawn to Elmyr for his villainous genius, likely admired the maverick, the pretender who duped the king makers. He was a crowd pleaser, as any conjurer is. Strangers showed up on his doorstep. “I read about you” they said “and I always wanted to have a Blue Period Picasso” or a Matisse … Modigliani…Renoir, etc. Rarely did their covetousness or curiosity stray into that little explored realm of original works in Elmyr’s own style. Even though his notoriety earned him an honest living for the first time in his life, it came at a price — vindication of his merit as an artist in his own right. He still felt like an outlier and was viewed similarly by the public, and a pariah to the people and institutions he defrauded. Emancipation from his reputation was the greatest struggle of his life.

It was an odd metamorphosis from the opprobrium of fraudster to underdog cast in a David versus Goliath mold… and my friendship with him was an improbable adventure. When asked if I felt any outrage about him being a con man, I replied no.

Art has a long subversive streak. That it breeds outliers and rule breakers is unsurprising. De Hory was one of them. Then, I was a product of the most socially turbulent decade of the century — the sixties. I eagerly embraced the counter culture. We championed rebels and that’s how I viewed Elmyr, as a kindred spirit, as someone who hoodwinked the establishment, exposed the fallibility of the cognoscenti, institutions and art dealers. So, his anti establishment activism held no shock value for me.

But I was never a victim of his larceny, though the strangest irony I witnessed was this: the man who lived by his wits and took advantage of the gullibility of his marks, was easily duped by others. It’s not hard to understand why many would view this as poetic justice, karmic payback, or that thieves deserve no sympathy.

However, I had insights that others did not; part of my newfound awareness was that the adage of things not necessarily being what they appear to be — was true. The world class scoundrel knew right from wrong, observed an almost-Victorian social code that valued propriety, civility and honor. He was generous to a fault and mindful of those less fortunate. He was, like most everyone, complex. I marveled at how so many disparate traits were housed in one body. And this paradox is what others recognized in themselves and perhaps were less condemning than what his criminality might evoke. And he was as prone to becoming the victim of misplaced trust as the rest of us. It was his former dealer and partner who betrayed him and ultimately orchestrated his death.

The art forger showed us a picture of ourselves — imperfect and wired to use deceit as a tool to serve one’s own interests — as anyone in a pinch might do.

For those not damaged or bothered by Elmyr’s exploits on the wrong side of law and order, maybe he set their streaks of insubordination aflutter. I sensed that the popular appeal of Elmyr’s saga resonated with the inner victim in everyone who felt thwarted, unrecognized, stymied by obstacles keeping one’s ambition in check. Even when that meant crossing the legal divide, becoming an outlaw, he knew first hand that there were profiteers on both sides of that line and gamesmanship that allowed them both to not just survive but thrive. The cautionary buyer beware warning expresses an embedded expectation that “a fool and his money are soon parted,” and this precept normalizes pretense and dishonesty. Elmyr forgave his criminal enterprise by saying, “I played by rules given me.” Remorse was not obligatory.

De Hory’s art and life had much in common, both embroidered by stagecraft and at times difficult to distinguish myth from the truth, but never straying far from the lie designed to guarantee survival. Given the choice of lying and thereby avoiding harsh consequences, most, I suspect, would feel little compunction to tell the truth, observe ethics, the law or be inconvenienced by forces impeding one’s self-interest. It’s only when we recognize the wrongness of our actions that we resort to excuse making. The French have a saying: qui s’excuse s’acccuse. He who excuses himself, accuses himself. It suggests a disincentive to apologize, take ownership of wrongdoing. Elmyr couched his stories, fact or fiction, in the palette of a gifted raconteur, and in the least incriminating ways possible, that his acts of defrauding others were low on the sin list and unoriginal. In a way, we all reconfigure our self-image to diminish our faults.

As we gain mastery of language and cunning that serve our designs, deception not only loses its sanctions, it becomes ubiquitous. When we identify those pathways that allow us to get what we want, we feel empowered. Never mind that individual success often collides with public interest. In the contest between sacrificing self-interest in favor of public well being, we only need to look in a mirror to see the winner. In other words, not doing the right thing is permissible as long as you win. That’s the main thing. And success breeds repetition… perhaps more so for tricksters.

This is what I came to better understand during my seven years in the company of a man whose life was rich in irony and contradictions, who brought a dignity to charlatanism, respect to dishonor, that life’s shades of gray force us to surrender to uncertainty over hubris or moral absolutes, to abandon the shibboleths behind specious judgments

In early 1970 I watched a film crew follow Elmyr with a camera on the Spanish island of Ibiza for three days. In the documentary they made, called: “Elmyr, The True Picture?” , he exhibited his charisma and talent as he created works in the manner of Modigliani, Matisse, and Picasso on demand. Spectators witnessing this act of prestidigitation might re-examine one’s reverence for the work of the original masters, or be awestruck for his nimble mimicry. One of the most enduring lessons he shared was: “Mark, never buy art for the price or name attached to it.” The man who forged success from forgery, cautioned against worshipping false gods. “ If you buy something you love,” he said, “you’ll never feel cheated.” That was his long-standing message. He reminded me of what we should feel— forget the branding, name-recognition snobbery, appreciate everything for the pleasure it brings. If his work were judged on its intrinsic merit alone, that leveled the playing field, one on which he thought he could compete… and succeed.

I was once invited to speak to a group of graphic artists about my experiences with Elmyr. I mentioned that I had recently seen an important Matisse exhibition and found some of his graphic works weak. I inflicted more pain, adding, “I think Elmyr was a stronger draftsman than Matisse.” Someone writhing in his chair took issue with my assertion. “Impossible,” he said, “It couldn’t be as good, as it wasn’t by the hand of the master,” He was willing to place more stock in authorship than intrinsic merit. And that misplaced trust may have played its part in Elmyr’s long running success as a con man. His pastiches had the patina of authenticity. In support of their believability, he asked with a pixieish grin, “Would you prefer a bad original to a good fake?”

He claimed more than once that he wasn’t an actor, though he was precisely that. He mirrored his target audience; he looked the part of dispossessed landed gentry; he spoke their language of connoisseurship and his art was convincing. It was a perfect storm: when covetousness and opportunity meet. Elmyr recognized that the marketplace was an incubator of opportunism where the quest for prestige or profit pushed all other concerns aside and the warning of caveat emptor was understood with a wink and a nod.

The indomitability of self-interest energizes the business world. Even when that meant crossing the legal divide, becoming an outlaw, he knew first hand that there were profiteers on both sides of that line and gamesmanship that allowed a symbiotic coexistence. This is why I view him more as a player than a perpetrator. He took advantage of a system that rewarded cleverness over honesty, one that provided little incentive for remorse. Then, when it came to forgiving his trespasses, he could be generous with himself.

Elmyr was adept at altering reality with the verve and panache of the painter he was. His self-made mythology about his life leaned heavily on artistic license and when he felt the truth was unkind to him, it was his purview to edit the facts. After all, that which is self-serving may be our most reliable compass, enabling us to rewrite our histories with an eye toward image polishing and diminish the pangs of conscience for our failures and missteps.

My thoughts and observations about how perception is a Pygmalion-type creation molded in our own self-image to suit our needs, are from an early chapter in my life. All these memories have an unanticipated relevance now as I revisit them. I have to take an honest look at my own shortcomings, my unaccountability, remembrances of things I’ve done and only now take ownership — a half-century late.

As I write these words, I’m on a plane heading for California to see my birth daughter whom I abandoned before she was born. Words can’t disguise that to make either of us feel better. I can only explain but not excuse myself. This is the best I can offer. Unlike Elmyr, I can’t take refuge in plausible deniability, knowing that I wronged someone and shunned culpability.

Now, I want to see if my newfound fatherhood will endure beyond experimentation to lifestyle and long delayed accountability come to roost.

Fake Fakes in the Forger’s Oeuvre

Posted on December 4, 2010.

One more story about Elmyr de Hory

by Johannes Rød

johannes.rod@getmail.no

Preprints of the IIC Nordic Group 16th Congress, Reykjavik, 2003, s. 53-57.

If an art forger becomes famous because of his ”dirty” business, his pictures, fake or not, surely attract the art buying public. The quality of the art work itself does not have to be the most important – but rather the story connected to it. For Elmyr de Hory, this was the actual situation at the end of the 1960s. Because of the legendary status he had achieved during his 20 year career as a forger, the market for his pictures as a normal artist was huge. But this was also a situation open for exploitation by other participants in the market.

The American oil-millionaire Algur Hurtle Meadows had from the beginning of the 1960s established a collection of more than 60 impressionist and neo-impressionist paintings. Most of them were purchased through the Parisian art dealer Fernand Legros. In 1967 experts from the Art Dealers Association of America (ADAA) evaluated the collection, and the verdict was shocking: 36 of the paintings were fakes. This was the incident that revealed one of the most famous art-fraud scandals in the twentieth century, and the involvement of the art dealers Fernand Legros and Real Lessard, and the art forger Elmyr de Hory or Elmyr von Houry, Elmyr Herzog, Elmyr Cassou, Elmyr Hoffman, Elmyr Raynal, Elmyr Dory–Boutin, Elemér Horthy as he also called himself. The forgeries were executed as pastiches, a principle Elmyr stuck to during his criminal career, he never copied master-paintings.

After the revelation, the trial was going to be held in France the following year with the 36 confiscated paintings as evidence. But an extradiction agreement did not exist between France and Spain at that time, so consequently, as long as he stayed inside Spain, Elmyr could go on with his life in freedom. The sudden death of Hurtle Meadows lead to a postponement of the trial, and Legros and Lessard got small sentences some years later. In his studio in Ibiza, however, Elmyr continued to paint pastiches as before – but with a slightly different finishing touch: he signed Elmyr. Until his death in 1976, this was his only occupation. The pastiches were popular among the public, and several galleries in Spain had them for sale the 1970s. In the 1980s, Sotheby’s and Christie’s in London put quite a few Elmyrs on auction, and in 1983, the estimates from Sotheby’s on each painting went from £ 500 up to £5000, and they were sold from £800 up to $3000. In the late 80s and beginning of the 90s the situation for works connected to Elmyr changed. First there was a profound increase in pastiches signed Elmyr on the market and secondly, quite a few forgeries signed Matisse, Modigliani, van Dogen etc. supposedly by Elmyr de Hory were put into the market. Sotheby’s in New York had to withdraw the painting Woman in an Interior signed Matisse 1943, because it was suspected to have been painted by Elmyr de Hory in the 1950s.

The painting Woman with Pearl Necklace signed van Dogen and painted by Elmyr in the 1960s was exhibited as a genuine painting in the Fauvism exhibition held in the Tel Aviv Museum of Art in 1996.

According to Sotheby’s in London, the auction firm stopped selling pastiches signed Elmyr in the early 1990s because the quality fluctuated so much – it was difficult to tell wether it was Elmyr’s work or not. The Galeria Es Molí in Ibiza reported the same chaotic situation for Elmyr’s work there. From the mid 80s until the early 90s, the average artistic quality for pictures connected to Elmyr de Hory had changed. In other words, it was difficult to tell whether a picture signed Elmyr was actually executed by Elmyr or not. It was difficult to tell whether a supposedly true forgery by Elmyr (painted before the revelation) actually was done by Elmyr de Hory. The only trustworthy reference material (36 fake paintings from the Algur Hurtle Meadows collection) were stored behind iron doors in the Palais Justice in Paris.

To make the situation even more complicated, the two art-dealers, Real Lessard and Fernand Legros, had their own versions of the art faking business they were a part of in the 1950’s and 60’s. In his book L’amour du Faux Lessard claimed that he was the artist behind the forgeries, and that Elmyr de Hory only made the fake signatures. In the book Tableaux de Chasse Legros claimed that Elmyr de Hory was a Hungarian art critic he met on Ibiza in 1963, and not a painter.

According to his biographer, Elmyr practiced several different faking methods in the 1950s and 60s. A potential sale was of course first and foremost dependent of the quality of the artwork itself, secondly how convincing a provenance he could make, and thirdly his own appearance. With his natural talent as an actor he presented himself as a distinguished European gentleman, dressed in tailor-made suits with a golden watch on a golden chain hanging from his waistcoat and with a characteristic Hungarian accent. This striking person who sold pictures from the remnants of the family collection that he managed to take out of Hungary before the communists invaded the country fooled a lot of people. When it came to the presentation of the actual ’work of art’, an important element was the artificial patina: If the painting was supposed to be painted in 1915, the material structure had to look like it. With the paintings in the Algur Hurtle Meadows collection this was partly done by a relining (if a painting is relined it looks more ’authentic’), and partly by using the right sort of materials (french type canvas and stretchers for the french paintings) patinated to give the illusion of age.

But one of the most successful methods, according to Elmyr, was to use old art books with folio photographs. Carefully the original photo was cut out and Elmyr produced a painting in the same style and with a similar representation as the original. Then Elmyr’s painting was photographed and carefully the new photo was glued into the book as a substitution for the original one. With the actual painting in one hand and the art book in the other – very few art dealers, according to Elmyr, hesitated to buy the fake painting if the price was good.

In the beginning of the 1980’s, when paintings connected with Elmyr de Hory gradually became more frequently found in auction-houses, galleries and art dealer’s stores, the situation was difficult for both dealers and buyers. The quality of the paintings varied, and it was hard to tell whether it was one of Elmyr’s or an art piece made by another person in the name of Elmyr (a faked Elmyr). The following note in Time Magazine in the 1980’s illustrates the situation:

… take a look at this rare collection of 100 paintings. Yessir, these are real beauts, all of them done in the inimitable styles of Picasso, Matisse, Modigliani and other early modern masters. Well, to be honest, not quite inimitable styles. The paintings are actually by a clever Hungarian counterfeiter, Elmyr de Hory. Considered the world’s premier art forger before his death in 1976 … Eventually de Hory was so famous that he began signing his ’fakes’, and many of them had found their way into the hands of John Connally. Now in partnership with Forrest Fenn, owner of a gallery in Santa Fe, New Mexico, the onetime Governor of Texas and presidential hopeful wants to sell off some of his acquisitions. Price $12.000 to $15.000 apiece. After all, argues Fenn, ’If they are as good as real, then what the hell are we talking about? I mean, what is art?

The Connally collection of 100 paintings was bought from a former english bookmaker, Ken Talbot, in 1983 for $225.000. Talbot claimed he bought 400 paintings from Elmyr de Hory in the 1970s for $350.000, and he described his relationship to art with the words: ’I wouldn’t have known a painting at the time if it fell on me head’.

In 1991, a new revised edition of Clifford Irvings book Fake from 1969 was published by a private publishing firm in London (Ken Talbots own firm): Enigma! The New Story of Elmyr de Hory. The Greatest Art Forger of our Time. Retold and presented by Ken Talbot. Irving confirms in an interview in 1996 that he had sold the rights to reissue his book to Ken Talbot: ”But I have never met him and I have never written any note to the new edition as it is printed in the book. It’s a literary fake.”

The book has 10 new color reproductions of paintings supposedly done by Elmyr as true fakes (prior to 1967). Six of them where present in the huge presentation of Elmyr de Hory in the gallery of the Tokyo newspaper Sankei Shimbun in 1994. The catalogue from this exhibition presents 70 forgeries by Elmyr de Hory from the collection of Ken Talbot. But the paintings however, are mostly badly executed copies of famous impressionistic and neo-impressionistic paintings, and some of the figures in the compositions also have prominent asian features. Here are some examples:

None of the 70 paintings have the slightest resemblance to the reference material in the former Meadows collection. Nor do they represent the level of quality typical of Elmyr’s work between 1967 and 1976. According to his flatmate on Ibiza from 1971-76, Mark Forgy, Elmyr never copied any particular painting, he painted in the style of other artists. Still more strange is it to read the preface to the catalogue from the Tokyo exhibition:

”We are exhibiting paintings done by Elmyr de Hory, a genius we will not like to be confronted with again. … The exhibition, for the first time in Japan, consists of more than 70 fakes of modernistic paintings among others masters such as van Gogh, Picasso, Matisse and Renoir. ’I am always painting in the style of other artists, I never copy [my italicize]. The only fake in my pictures are the signatures’, de Hory says.”

It is likely that none of the paintings in the ownership of Connally, Forrest or Talbot were truly fakes by Elmyr de Hory: None of them were painted with the intention of being an original masterpiece and signed as such: the pictures were all badly executed copies or pastiches. A question to ask is if they were painted by Elmyr at all? Both Clifford Irving and Elmyr’s closest friends in Ibiza express their profound doubts. Vicente Ribas, attorney and close friend of Elmyr, claims that Elmyr only did as much painting in the 1970s as he found necessary for a comfortable life. He was mostly interested in socializing and going to parties, and did not paint much.

Theory of modus operandi: The Ken Talbot Affair

The findings and the information in this affair are quite contradictory and confusing. First and foremost, Elmyr de Hory’s closest friends on Ibiza claim that he could not have painted what Talbot claims he had, and certainly not such a great number. Sotheby’s David Breuer-Wild supports their view in connection with the quality of the Talbot paintings and refers to what he has seen by Elmyr de Hory on the art-market. My research on the paintings from the Meadows collection reinforces his view. The preface to the catalogue from the Tokyo-exhibition quotes Elmyr saying he never copied; nevertheless the exhibition itself is full of poorly painted copies. The asian ”look” in the Matisses and Modiglianis also provides circumstantial evidence that the paintings were manufactured geographically far from Ibiza.

In conclusion my theory of Ken Talbot’s modus operandi is that he exploited the market to sell cheaply produced (may be painted in an Asian country) copies and pastiches as paintings done by Elmyr de Hory. These paintings were not individually very expensive to buy (about £800-£5000), but in large numbers the business generated must have been quite prosperous. With the reissue of Clifford Irving’s book with 10 new color reproductions and with the 70 works in the catalogue from the Tokyo-exhibition, he might have tried to ”authorize” paintings in his ownership as ”genuine forgeries” done by de Hory. In this way he might have ”produced” fake fakes using the same method of presentation in art books as Legros, Lessard and de Hory used when they produced and sold fakes in the 1960s.

Everything connected to Elmyr de Hory involves an element of fiction. One can never tell what is actually true and what is not: he faked his own date of birth, he faked his family background in Hungary, his own biographer Clifford Irving was sent to prison for trying to write a false biography of Howard Hughes – and after his death Elmyr’s oeuvre is growing bigger and bigger.

“I prefer the buffet in my dining room.”

Posted on December 3, 2010.

By Mark Forgy

Pull out those forgotten matador lamps from the attic with those pink ruffled shades, the ones worn as hats by your drunken relatives on New Years Eve. Have I got the perfect center piece for you!

Someone sent me a notice of an auction featuring a “Bernard Buffet” purportedly by Elmyr. The subject: a butterfly. Now, I’ve become accustomed to seeing many garish works sporting the name “Elmyr” scribbled by third-graders for the pleasure of discerning art lovers. However, I believe they have not yet invented a unit of measurement small enough to assign the chances of this painting actually being by Elmyr, or, at least, by the Elmyr de Hory I knew.

Elmyr and I were guests on a yacht (well, a small ocean liner) while in Capri. The owner bought it from Buffet and it still had some Buffet oils hanging inside. Looking them over for a moment, Elmyr turned to our host and said “If these came with the yacht, I hope you got it at a reduced price!” Not only did he loathe Buffet, he was at a loss to understand why anyone would buy his work. I’m sure he thought no self-respecting bordello owner would cheapen it by having a Buffet on its walls. He also told our host “I prefer the buffet in my dining room.” Just trying to put this in proper perspective.

“… You Don’t Know Me, But …”

Posted on June 14, 2010.

By Mark Forgy

The recent exhibition of Elmyr’s art at the Hillstrom Museum of Art in Minnesota yielded unexpected surprises. Newspaper articles about the show caught the attention of two people who in turn contacted me. I didn’t know their initiatives would spawn new friendships and lead to unlocking secrets I once thought impenetrable. But that’s the way of the universe, karma, or divine order, that one’s life can take a right-angle turn in an instant.

Answering the phone with an unsuspecting, “Hello?” I heard a man’s radio-quality voice; his tone would calm an agitated cat. He introduced himself and followed with the caveat “You don’t know me, but I read the article in the Star Tribune and just wanted to tell you that I knew Elmyr.” Jerry was his name and a swarm of angry bees could not have diverted my attention from that point on. “When did know Elmyr?” I asked him. “I first met Elmyr in 1964 or ’65 in California,” Jerry told me. For the next hour and a half I learned unknown details about the man I knew better than anyone else. Or so I thought.

Around this time I discovered there was another intriguing work, a portrait of a woman a la Modigliani, by Elmyr on display in an exhibition at the National Museum of Crime and Punishment in Washington DC. The show, a rogues’ gallery of perpetrators of art fakes, forgeries, and thefts, was the brainchild of its attractive, no-nonsense curator, Colette Loll Marvin. She, I discovered, is the director of public and institutional relations for ARCA (Association for Research on Crime against Art), a think tank dedicated to the detection, prevention of art crimes, cultural property protection, education, consultancy and advocacy. These savvy sentinels of artistic patrimony quickly spotted the cluster of artwork by Elmyr on their radar.

Marvin and her associate, investigator Allen Urtecho Olson, flew to Minnesota in April to view for themselves my collection at the Hillstrom Museum. My friend, Jeff Oppenheim, a filmmaker from New York arrived at the same time to film the exhibition before it closed. The timing of their visits could not have been better. Jerry also drove up from Kentucky to join the convocation of the curious; this led to an instant connection of people impassioned by art, all of whom realized that Elmyr’s story was not just incomplete but merited a fresh look and impartial examination to get to the truth, separate reality from folklore and find the facts behind the myth of the greatest art forger of the twentieth century.

This compelling journey is entitled: CHASING ELMYR, a new documentary offering never-before-revealed personal accounts, interviews, archival research, expert opinion on the societal implications of his illicit career, the complicity of greed: the art world’s seamier side. We will also take a look at the manufacture of the “value” placed on art, its influence on the proliferation of art crimes and the challenges they present.

Fake Elmyrs?

Posted on May 26, 2010.

By Mark Forgy

I recall an evening at Elmyr’s villa, La Falaise, during which I asked him what he thought about the prospect of others creating fake Elmyrs. He looked at me; his expressionless face suggested I had asked a silly question. A bemused grin then disarmed the awkward silence and we laughed together, enjoying the irony and unlikelihood of such a notion.

If I learned anything from my long friendship with Elmyr it should be this: self-interest is ever-inventive, plumbing the depths of imagination, resourcefulness, and most often trumps convention, ethics, or the law. Throw in an element of desperation, as Elmyr knew too well, then those mechanisms, legal or moral that keep people honest become minor inconveniences and ineffective inhibitors. Nor did I ever think I would find myself in the peculiar position of attempting to segregate …authentic fakes…from inauthentic fakes, an oxymoronic concept and surreal pursuit.

However, it is this strange situation that prompted me to create my website and source for those interested in viewing Elmyr’s bona fide works. Curiously, I find the idea of Elmyr’s saga being used as a template, or inspiration for others to exercise their own attempts at fakery much less alarming than the disturbingly awful refrigerator art being passed off…as Elmyr’s works. Nevertheless, from what I’ve seen on online auctions and elsewhere, this cottage industry is robust.

Elmyr always acknowledged that his sin was unoriginal. History abounds with artists dedicated to deceiving and profiting from unwary buyers. The bottom line here is that talent was the foundation of Elmyr’s long-running success as the twentieth century’s greatest art forger. Furthermore, if his imitators possessed his skill, I would feel less compelled to cry ‘fowl’.

My only hope is that those wishing to buy art they believe to be by Elmyr, they look here first.